Antisemitism in gaming

References

Yiannopoulos, Milo (2014). Feminist Bullies Tearing the Video Game Industry Apart. Breitbart. 1 September 2014. Available at: <https://www.breitbart.com/europe/2014/09/01/Lying-Greedy-Promiscuous-Feminist-Bullies-are-Tearing-the-Video-Game-Industry-Apart/>

Ullman, Jeremy (2020). Understanding the Antisemitic History of the “Hooked Nose” Stereotype. Media Diversity Institute. 29 September 2020. Available at: <https://www.media-diversity.org/understanding-the-antisemitic-history-of-the-hooked-nose-stereotype/>

Thin Blue Lines Fanpage (2020). 28 September. Facebook. Available at: <https://www.facebook.com/LEOBlueLine/photos/a.1271769949647193/1746373732186810/?type=3&theater>

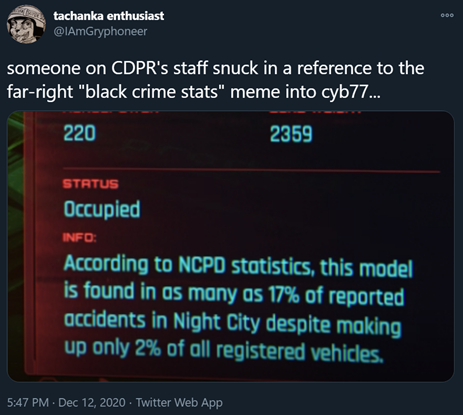

@IAmGryphoneer, someone on CDPR's staff snuck in a reference to the far-right "black crime stats" meme into cyb77…, Tweet, 12 December 2020, <https://twitter.com/IAmGryphoneer/status/1337816460689813504>

With the growth of the gaming industry, the expansion of media journalism can be seen to reflect the fact that video games are increasingly thought of as valuable storytelling mediums in their own right. The growing focus on story-driven narrations in gaming refutes prior claims they are merely a shallow pastime, pushing a multi-billion-dollar industry to consistently greater heights. Such recognition comes with its own problems – technological advances and graphical hyperrealism bring with them accusations of training players to display aggression, which manifest in acts of violence. This rhetoric was central to the notorious 2011 Oslo attacks revolving around far-right terrorist Anders Breivik – despite proudly identifying as a fascist and ethno-nationalist, many news outlets were stuck to the potential detrimental effect video games had on personal development.

Whereas it can be disputed whether videogames are directly responsible for condoning violence, there is a case to be made when it comes to the forms of violence they legitimize. The unfaltering popularity of first-person military shooters such as Call of Duty is indicative of the close links the industry has with army recruitment schemes, in a similar line to the funding of Marvel films by the US military – forming a military-entertainment complex wherein their imperialistic action appears justified. The inclusion of such messages within gaming speaks towards the wider network in which avid, self-branded ‘gamers’ congregate. Therefore, this is a line of argument that reaches beyond videogames, requiring an in-depth look at the issue at its root: understanding the culture surrounding gaming as one where extremist sentiment is allowed to thrive.

Gaming circles have become increasingly focused on establishing bonds of kinship amongst its members, perhaps as a stand-in for real-life estrangement. It is an ideological breeding ground, with members gravitating towards fascism and white supremacy, given new life and purpose in the digital age. It is hardly unsurprising that this is the platform of choice for reactionary movements; the rhetoric of nationalism goes hand-in-hand with depictions of heroic defenders of freedom and nostalgic settings of old. Populism thrives in such narratives, and the ability to put oneself firmly in the setting of the escapist fantasy through controlling the player-character plays a role in determining why gamers have a proclivity towards such external influences.

The coded language and iconography of the alt-right dogwhistle is a particularly insidious way of developing unity, whereby those acting as alt-right ‘recruiters’ may not even be aware of the fact that they are facilitating the trends of the movement. This may take the form of anything between engagement with large-scale and persistent harassment campaigns such as 2014’s GamerGate – which still feels its repercussions in the community today – to the circulation of seemingly innocuous internet memes. These include, but are not limited to, variations on the popular Wojak meme such as the Trad Wife or Nordic man: depicting an image of a blond, blue-eyed character that is often accompanied by a caption that shows a desire to return to ‘traditional’ family values, frequently disparaging the lifestyle of female sex workers, and other such individuals deemed ‘degenerate’. If pictures of a stoic man with archetypal ‘Aryan’ features weren’t enough of a red flag, such content imagines the world under a strict dichotomy between the righteous traditional coupling of generations past and their depraved modern counterparts – who are depicted as self-indulgent and wholly responsible for their own limitations through becoming aimless and adhering to leftist praxis and its dissociation from the capitalistic notion of ‘productivity’.

The comics take on a mocking tone as they chastise millennials for not being industrious, married homeowners with clearly defined gender roles in their 20s and 30s. The solution to their woes, thereby, is clearly to revert to the ‘old’ style of conformity, which allows people to live a fulfilling life in the knowledge they are contributing to the betterment of society. The normalisation of such messages, entrenched in white supremacy, reactionary politics, and an us-versus-them mentality, remains largely pervasive in the gaming community. When made to confront the changing face of video games, in which marginalized groups are increasingly brought to the forefront – whether through tokenism or an earnest desire for representation – the ‘erasure’ of the male power fantasy that preceded them is taken as a personal attack, in a similar manner to the dichotomy created by the Wojak meme. Long-standing franchises such as Mortal Kombat have been accused of pandering to intrusive feminists in the latest installation, through their redesigns of iconic female characters such as Kitana, removing many of the markedly orientalist and overtly sexualised aspects of her appearance. Many have decried the fact that the new designs have stripped the series of one of its main appeals, estranging its primary male demographic in the process.

However, such incidents are overt and widely-reported on. Journalists such as Milo Yiannopoulos have built entire careers upon inflammatory statements made against ‘an army of sociopathic feminist programmers and campaigners’ who they imagine to be the true enemy of gaming – and even society at large. What is less acknowledged is the antisemitism that permeates such spaces; either through invoking obvious stereotypes in a Jewish-coded figure or in more overt instances of political allegory. When political correctness is deemed to be a hindrance to freedom, accusations of ‘Cultural Marxism’ draw marginalised groups together under one framework that supposedly seeks to contend with and replace the current order of things in the Western world, diminishing the role conservatives and white men have to play in the process. Harvard professor Samuel Moyn makes the case that Cultural Marxism is an updated spin on the Judeobolshevik myth of the post-Russian Revolution era, which made the claim that ‘the instigators of communism were the Jews as a whole…conniving as a people to bring communist irreligion and revolution worldwide’. Without action taken to stamp out such movements at their root, their effect will only continue to be felt – with video games serving as a prime medium for the subconscious influence that dogwhistles afford.

Furthermore, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement gaining rapid traction in the past year, a multitude of internet memes have resurfaced in an attempt to define video game spaces as singularly white supremacist spaces. When many see its community as bound by the kinship that shared ideology and white gamer ‘identity’ allow, those who do not readily fit into such definitions are viewed as intrusive – or trying to ‘politicize’ gaming where there had apparently never been any political implications previously (as if a whole art form is capable of existing without wider contextualisation!).

A viral meme in support of Law Enforcement makes the incorrect claim that black people are disproportionately responsible for a majority of homicide incidents in the USA. The image is often accompanied by captions willing people to assess media bias, which is imagined as overwrought by those seeking to reshape white people into a ‘subaltern’ class. Such conspiracy theories are inextricably linked to strains of antisemitic propaganda, which would have people believe the world is run by an elite class of celebrity figureheads or ‘lizardpeople’ who have an unrelenting grip on the press. Following industrialisation and modernity making print publication more accessible, the first widespread conspiracy came in the form of a Russian antisemitic canard titled ‘The Protocol of the Elders of Zion’: detailing Jewish plans for a global takeover of the economy and mass media. American industrialist Henry Ford believed it to be such essential reading that he facilitated its legacy through personally funding its distribution across the United States in the 1920s – establishing the Jewish as a discrepancy and a threat to the capitalist order he was trying to produce.

The screenshot, taken from this year’s highly-awaited role-playing action title Cyberpunk 2077, utilises a play on an internet meme that has achieved notoriety through its manipulation in the hands of white supremacists. It references a common alt-right talking point, of bringing up unsourced claims that ‘black people commit (x)% of crimes despite making up only (y)% of the population’ – but the ‘joke’ is only evident to those who were clued in prior to reading the journal entry. The nature of this type of dogwhistle is one that does not seek to recruit, but rather to reinforce the solidarity between those in-the-know. Naturally, the meaning and intent can be contested – but the fact remains that the game has come under fire for its tone-deaf portrayal of law enforcement in a dystopian setting, counteracting and demeaning the entire project of ‘cyberpunk’, which seeks to depict the lives of the marginalised whilst critiquing the role the surveillance state has on maintaining their subjugated positionally.

One of the most predominant depictions of antisemitism that goes largely unnoticed occurs within The Witcher franchise, adapted from Andrzej Sapkowski’s novels by Polish studio CD Projekt Red – the same studio also responsible for Cyberpunk 2077. The depiction of their fictional elven race as victims of a genocide is problematised through the invocation of the word ‘pogrom’, which is a word commonly denoting the large-scale eradication of Jewish peoples.

The elves and dwarves who chose to remain in human settlements ‘coexist’ through enforced segregation into ghettos, whereas those in the Scoia’tael guerrilla forces who choose to revolt against their oppressors are branded terrorists and anti-heroes; forgoing morality for their end goal. Sapkowski’s writing is undoubtedly influenced by Poland’s broad history of occupation and persecution, but (despite violence and political strife being commonplace) delegitimises the processes of revolution in its portrayal. The culminating image, of freedom fighters who indiscriminately pillage and murder for their cause – such as The Witcher 2’s bandit leader Iorveth – is a cheap way to write in moral conflict, demonising the subaltern class in the process.

Fantasy racism is not exclusive to the gaming community but has played a significant role when it comes to normalising radicalised physiognomy as an indicator of personal morality. The RPG genre is rife with depictions of uncivilised, tribal antagonists with hulking bodies; or following from common tropes through depicting goblin bankers with hooked noses. Why then, do fantastical settings seem so intent on reproducing real-world injustices for the sake of making their settings appear gritty and realistic? Readings in good faith could take such tropes as divorced from reality, along the same line as J.R.R. Tolkien making the case that Lord of the Rings is intended to be read as a standalone, removed from all real-world implications, and therefore should not be understood as an allegorical writing. However, saying this does not necessarily make it devoid of meaning – unconscious bias stemming from the author’s experiences can manifest in their writing regardless. Whereas this is not strictly defined as allegory (which implies authorial intent), its applicability to real life problematises the writing regardless.

The evidence suggests that it remains prevalent for writers to use gaming as a platform to air their personal prejudices. Neither should this be mistaken as ‘representation’, which would be saying that we equate Jewish people with non-human races or monsters. Here, Dr. Dave Rich of the Community Security Trust warns of ‘caricatures of Jews with grotesque features, and specifically with large noses’ acting as a reiteration of the caricatures used in Nazi propaganda. Therefore, it is important to assess and challenge the antisemitism that seeps into the everyday because of its direct correlations with white supremacy, or a pervasive conceptualisation of blond-haired, blue-eyed whiteness as normative.

Written by Jasmine Joshi