Black Political Struggle and its Iconography

Black political struggle and its imagery have routinely been co-opted by pop-culture, through art, film, music and sport; In the modern day, the term ‘Black Panther’ is far more likely to conjure images of Chadwick Boseman and Ryan Coogler, than Fred Hampton or a Free Breakfast Program. The iconography, emotions and narratives of Black Political Struggle have soaked themselves into Western popular culture, becoming culturally ubiquitous for their aesthetics.This has been the story of every major Black Political movement of the last 70 years, encompassing the Civil Rights movement of the American South, the Black marxist/Panther movements of the 1970’s, Thomas Sankara’s Burkina Faso and many, many others. It must be addressed however, that these aesthetics are often taken at face value, frequently being manipulated and distorted. It must also be said that this is not a coincidence, as dealing with the representation or image of political anger is significantly easier than addressing the cause of this anger. The tale of Black Political Struggle in the 20th Century has largely been told through the iconography associated with its various movements/groups and how they have been represented through images recreated separate from the context that birthed them; this can be seen most directly through how the Black Panther Party is seen in the modern day, due to films like ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’ or ‘Blackkklansman’, rather than the political philosophy of its members.

Political struggles have always been narrativised, in an effort to understand them in their entirety. This narrativisation is mostly produced through film, literature and photography, giving both a visual and written aesthetic to a specific period of time. In the 21st century, as we have become significantly more inundated with information and visual imagery on a daily basis, the aesthetics of certain historical periods have become instantly recognisable and hyper specific. This is mostly due to the media we associate with this time period, rather than the time period in earnest; it is likely that if you asked someone in their mid 20’s to describe the fashion and aesthetics of the 1920’s, they would lean heavily on the world created by F. Scott Fitzgerald in “The Great Gatsby”. The same can be said for much of the 1960’s and 70’s, where the aestheticisation and narrativisation of these periods has created a false consciousness, destroying a true history and understanding of these eras. It must be said that this narrativisation is often presenting a warped or bastardised version of history, relying on style and imagery rather than accurately contextualising an event. These decades are of particular note, as this is where Black Political Action in the West derives much of its identity; Movements like the Black Unity and Freedom Party and the Black Panther Party very much canonised the image of Black Political collectivised action.

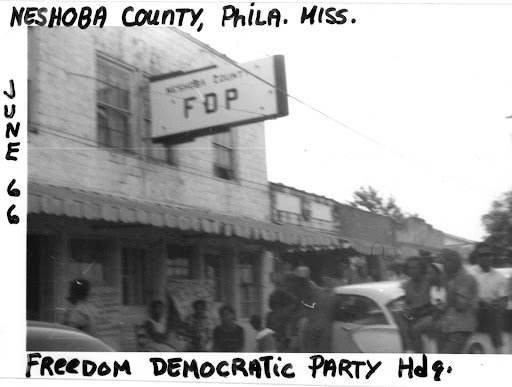

In the modern day it can be seen how the narrative of the American Civil Rights movement of the 1950’s and 60’s is presented in popular culture, with a reliance on Black and White Imagery and poorly maintained audio recordings in an effort to ‘date’ the movement further. This is a deliberate attempt to manipulate the imagery associated with Martin Luther King, Selma and the many participants of the movement, to place them and the factors that created them further from our modern day standards of morality or political correctness. The iconography of various Black Political movements have been consciously manipulated and recreated in an effort to retell and restructure the history surrounding them. Specifically throughout the mid 20th century, this was a concerted effort to underplay the influence of Marxism in the ideology of Black Political struggle at the height of the cold war.

With this said, the idea of illegitimising and criminalising Black Political Anger is at the heart of this retelling. The iconography of Black Political struggle is routinely distorted in an effort to present Black expressions of political autonomy as unlawful, fruitless and unjustified, be it through censorship or through recontextualisation. One example of this can be seen in the discourse surrounding the London Riots, where Mark Duggan was represented continuously as a criminal deserving of his fate at the hands of the Police, rather than as a member of a highly persecuted political minority. By presenting Duggan as a criminal, instead of the victim of a political murder, the British Government and media were able to present the riots as Illegal or unjustifiable, in an effort to limit the potential for lasting political reform in its aftermath. This was a recurring trend throughout the 20th century, seen through the response to both the British and American Black Panther Parties, the 1985 Broadwater Farm Disorders and the various ‘Race Riots’ throughout America between 1900 and 1950. Into the modern day, this type of response is still seen, most recently in response to the BLM Protests and Riots seen throughout the Western World.

Conversely, the image of the ‘Black Revolutionary’ in the 20th Century has been seen throughout the media to martyrise various political figures. This can be seen in the lasting imagery associated with Thomas Sankara, 1st President of Burkina Faso, following his death at the hands of a coup in October 1987. Noted for his anti-imperialist and self-deterministic foreign policy, Sankara’s greatest impact as a political figure is not seen in his ideology, but rather in the potential that his career represented. Sankara exists, in a similar mode to Tupac Shakur and many others who ‘died too young’, as the object of infinite potential, and it is in this potential that many Black activists, ideologues and intellectuals have attached themselves. The same can be said for both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, with both men surviving in popular consciousness due to the untimely nature of their deaths, alongside their activism and political action whilst alive.

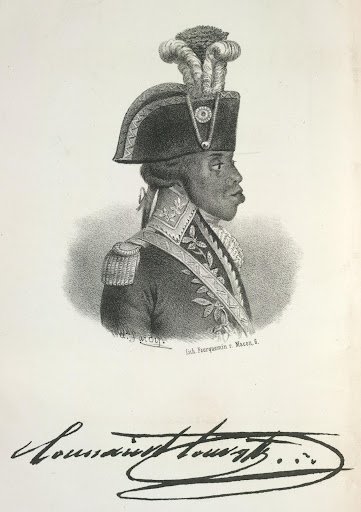

Within the idea of the Black Revolutionary is the core tenet and principle of sacrificing one’s life for a greater purpose, presenting oneself in the place of others in order to achieve a higher political goal. Through death these men were elevated to the status of legend, becoming aestheticised as the positive ideal of the ‘productive Black Revolutionary’; to some, the end goal of the Black Revolutionary is inevitably death. There is a long track record of this within the greater Black Political consciousness, with notable examples seen in the Haitan Revolution and Toussaint Louverture and Nat Turner and the Turner Rebellion. Martyrs represent key reference points for Black Political Struggle with Thomas Sankara, Luther King, Fred Hampton and Huey P. Newton all finding great influence in death.

Celebrities and athletes, figures peripheral to political action, have also seen themselves become part of the cultural canon associated with Black Political Action. This can most famously be seen in Muhammed Ali and Sydney Poitier, all of whom represent examples of political action and consciousness in popular culture. In one way or another, these men all became emblematic of how far reaching and universal Blackness is, signifying to the cultural zeitgeist that fame does not remove you from political life. Specifically in the case of Muhammed Ali (fka. Cassius Clay), he was a highly politicised figure in his era, in some sense representing the archetypal ‘politically conscious athlete’, setting a model that many have followed since. It is not unfair or unjust to suggest that a large part of his sporting legacy and its everlasting impact, is also owed to his status as a Black Political hallmark. The same can be said for Poitier, an actor who continuously engaged with the realities of Black Life in America through his work. Due to the subject matter of his films, most notably Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and The Defiant Ones (1958), Poitier notably gave a face or body through which many Americans could see themselves. In a more abstract sense, Poitier represented breaking through a glass ceiling for many, speaking to the most common of human experiences - becoming a universally understood reference point for Black Creatives and Activists.

There are a number of key symbols and cultural identifiers that have survived into the 21st century, with a direct throughline to the Black Political Struggle of the 20th Century. An example of this can be seen in the iconic ‘Black Power Fist’, a symbol that has seen itself become universally understood as a signifier of Black Political action. Though the action itself has roots in more general revolutionary and anti-fascist political movements throughout Europe in the early 20th Century, towards the latter half of the century it became an overtly ‘black’ symbol. As mentioned earlier, sport had a massive role to play in this, thanks to the efforts of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City; having won Gold and Bronze respectively in the Men’s 200m, both men presented a black gloved fist as an example of political defiance. Although Smith would later state that it was a general action towards Human Rights awareness, it remains one of the most overtly political and instantly recognisable moments in Olympic History, representing a pop cultural reference point for political iconography. As evidenced by the BLM protests in both the UK and US, the symbol retains its value as an identifier of Black Political Action.

An understanding of the symbolism, iconography and imagery associated with the Universal Black Political Struggle affords us a deeper conceptualisation of its course and eventual outcome. By charting the various elements that make up the cultural canon associated with Black political action and how they are used, by both its heralds and detractors, a greater context is painted. The importance of this context cannot be underplayed, as it represents the bedrock for true change and meaningful political action.

Written by Joseph Yorke-Westcott